It is difficult to trace the June 2020 progress made by student organizers on the groun d in Minneapolis to any specific organization. Rather, I will look at the results and effects of student-based grassroots organizing and mobilization in Minneapolis before examining the formal organizations also on the ground in Minneapolis. Student organizing has recently achieved significant accomplishments in Minneapolis, with student activists pushing for the Minneapolis City Council to cancel the school district’s contract with the Minneapolis Police Department (Retta, 2020). Even before the murder of George Floyd and ensuing protests, the school board was already hesitant about renewing the police contract as a result of student pressure (Retta, 2020). Thus, while student-run organizations in Minneapolis have long exerted pressure to remove SROs and SLOs, the murder of George Floyd led to increased pressure by students on the school board to finally affect the change (Retta, 2020). Describing the process of protesting to get police out of Minneapolis public schools, high school junior Nathaniel Greene shared,

d in Minneapolis to any specific organization. Rather, I will look at the results and effects of student-based grassroots organizing and mobilization in Minneapolis before examining the formal organizations also on the ground in Minneapolis. Student organizing has recently achieved significant accomplishments in Minneapolis, with student activists pushing for the Minneapolis City Council to cancel the school district’s contract with the Minneapolis Police Department (Retta, 2020). Even before the murder of George Floyd and ensuing protests, the school board was already hesitant about renewing the police contract as a result of student pressure (Retta, 2020). Thus, while student-run organizations in Minneapolis have long exerted pressure to remove SROs and SLOs, the murder of George Floyd led to increased pressure by students on the school board to finally affect the change (Retta, 2020). Describing the process of protesting to get police out of Minneapolis public schools, high school junior Nathaniel Greene shared,

In the three months we’ve been out of school, students have been pepper-sprayed and tear gassed by the police or have seen the National Guard or the KKK rolling down their neighborhood. Police presence doesn’t make any of us feel safer, and I’m glad we no longer have to deal with it in school. (Retta, 2020)

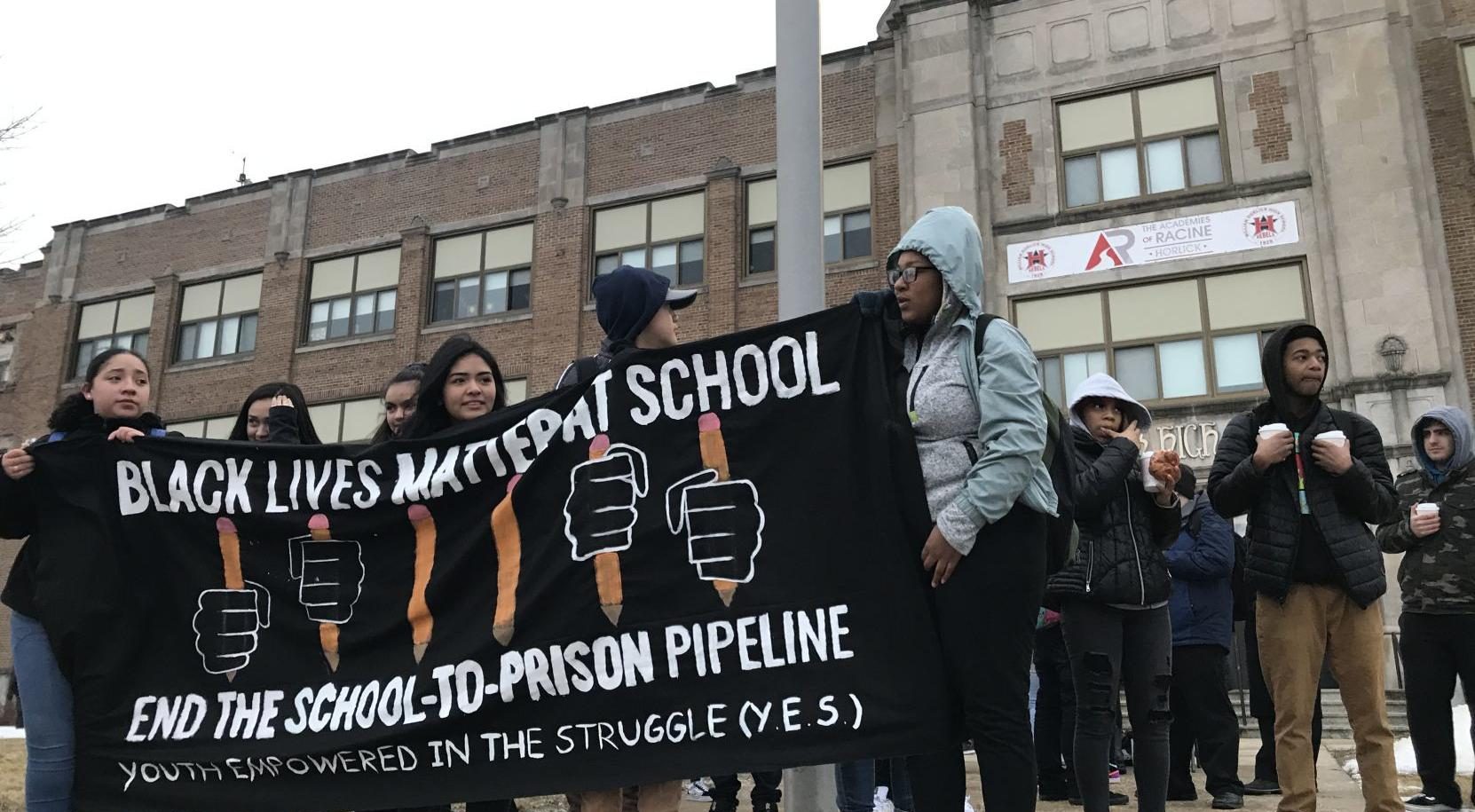

Furthermore, beyond large-scale protests against over-policing in schools, students of color have also used public pressure to leverage their way onto local school boards (Retta, 2020). Once there, they have been stark advocates for cutting the district’s SRO/SLO contract with the Minneapolis Police Department and changing other policies that would help curb the school-to-prison pipeline (Retta, 2020).

No contract means an absence of SROs and SLOs that are affiliated with police departments in schools, hopefully significantly decreasing the amount of referrals to the criminal justice system. While this change undoubtedly represents a huge victory for decreasing the school-to-prison nexus, challenges still appear on the horizon. Even on the same night as cutting ties with the Minneapolis Police Department, the Minneapolis Public School Board voted against multiple amendments that would have increased much needed funding for mental health resources, restorative justice practices, and community partnerships (Blad, 2020). Furthermore, beyond punting issues of student mental health down the road, Minneapolis plans to hire additional law enforcement personnel who will neither be members of the Minneapolis Police Department nor carry a weapon (Lahm, 2020). Despite these differences, however, the duties sound practically identical to those of traditional SROs/SLOs (Lahm, 2020). Indeed, a local student organizer said in an interview with a local newspaper that these alternate, private security forces “[are] just another way of being able to police and surveil students, especially students of color” (Kierblier, 2020).

In addition to grassroots student organizing, the Minneapolis-based chapter of the Students for Educational Reform Program also played a key role in advocating for and advancing change. This group seeks to place students at the center of organizing efforts to lessen police presence and to fight against zero tolerance policies in schools. Critically, one of the main ideas on their website is that the organization exists “by and for the community’s students,” placing both the community and students at the center of the organization (Students for Educational Reform). This mirrors the organizing work of Ella Baker who sought to engage large numbers of the community in order to meaningfully confront oppressive power (Payne, 1989). Furthermore, this organization, which has national chapters, gives local power to its branches to engage in community initiatives, much like Baker pushed the NAACP to do so when she worked there (Payne, 1989).

However, while a local branch of the Students for Educational Reform may advocate for positive reforms, the national branch is an astroturf organization that often makes some concerning demands. As an astroturf organization, the national chapter intends to appear as though its demands come from the grassroots in order to give credibility to the national group who wants to withhold information about donor lists or make underlying policy demands. Thus, while the local Students for Educational Reform Program organizers in Minneapolis advocated for abolishment of police involvement in schools, the national, astroturf organization advocated for the reinstatement of the contract with the Minneapolis Police Department, while calling for rethinking the way police are utilized (Abdullahi, 2020).