NATIONAL CONTEXT — USA

Following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers on May 25, 2020, student activists across the United States have raised their voices in protesting the presence of law enforcement in their school communities (Reilly, 2020). Despite this recent uprising, the presence of school resource officers — a euphemism for police — in schools is not a new phenomenon. Over the past 15 years, the number of full- and part-time school resource officers (SROs) has increased considerably (Crime and Safety, n.d.). Today, school resource officers are present in about 45% of public schools, and 1.7 million students attend schools that employ police officers but no counselors (Reilly, 2020). The fundamental role that SROs play in the school-to-prison pipeline makes their presence in schools extremely concerning. Rather than protect students, police officers often create school environments in which students, especially students of color and students with disabilities, feel unjustly criminalized and unfairly targeted, jeopardizing students’ ability to learn. On top of this, the money schools spend on employing police officers could be diverted towards restorative justice practices and counseling services; resources that help create environments conducive to learning and in which students can feel safe, heard, and respected.

LOCAL CONTEXT — Chicago, IL

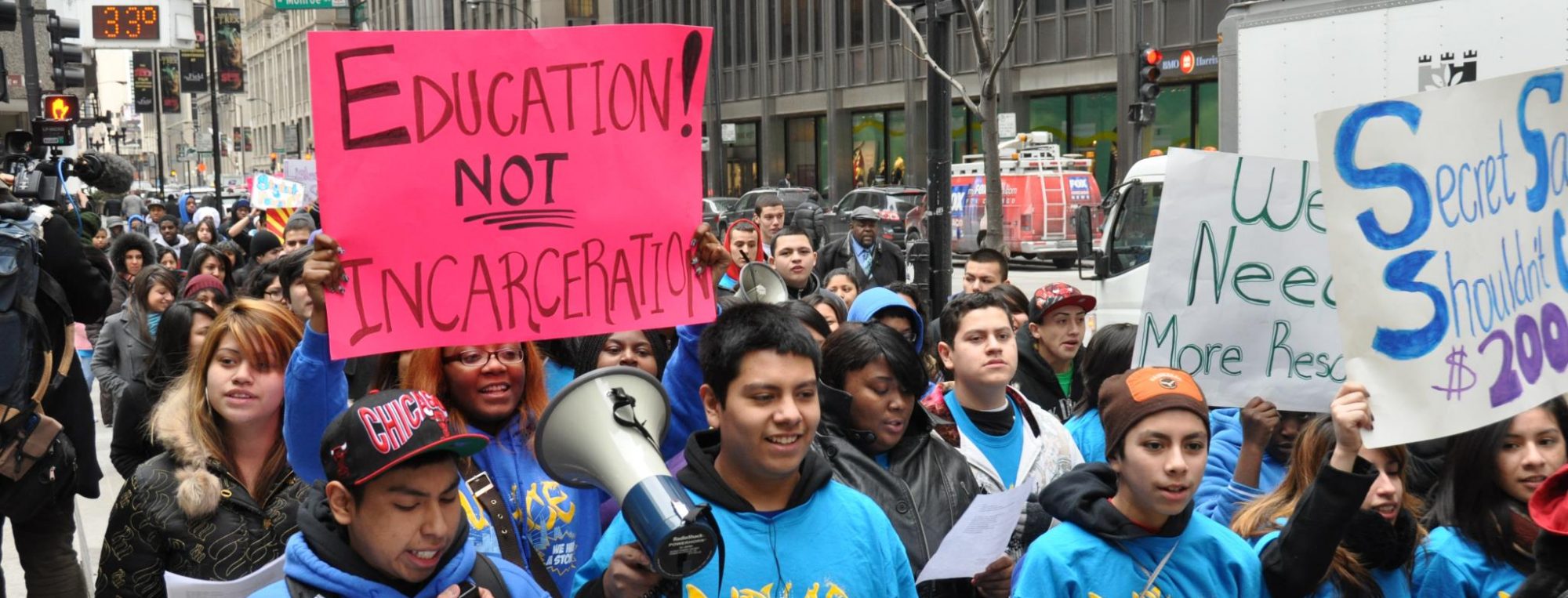

By enrollment, Chicago constitutes the third largest public school district in the US (United States, US Census Bureau, 2019) and every year, the Chicago public school system spends upwards of $33 million to sustain their contract with the city’s police department (Southorn, 2020). In 2017, the US Department of Justice found that Chicago spends an inordinate amount of money on settlements with civilians over policing and found patterns of racist policing practices (Sawchuk, 2019). Additionally, reports that have been published over the past two years by the city’s Office of the Inspector General found that there is very inadequate training for police officers stationed in schools (Lipari, 2018). Taken together, these factors paint a bleak picture of how police officers contribute to Chicago public school communities. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many grassroots organizations have emerged in response to the school district’s direct investment in the school-to-prison pipeline. One of these such groups is Voices of Youth in Chicago Education (VOYCE).